Topic 4.5 Maritime Empires Maintained and Developed

Before 1200, Europe’s economy was primarily feudal; agriculture was the basic means of wealth production, economic exchanges were local, and people bartered for most things they needed. By 1450 towns had recovered from the Black Death. Kingdoms were consolidating, and Europe was on the cusp of an age of exploration. The new view of wealth shared by Europe’s competing monarchs was based on the belief that wealth was primarily measured by one’s possession of gold and silver—tangible items that were static and finite. The more one kingdom acquired, the less there was available for the others. This economic principle, called mercantilism, led kings to drastically limit what they purchased from other kingdoms. Exports were good, imports bad. In this context, colonies became the key to a thriving economy. Instead of purchasing needed goods from another kingdom—an exchange involving the transferal of gold and silver to one’s competitor—colonies were managed to provide the needs of the mother country.

A prime example of mercantile policies was the series of Navigation Acts passed by the British in 1651 and 1660. Intended to stop the “leak” of goods from Britain’s grip of its American colonies, these acts required all goods from the colonies to flow directly to England. Despite the fact that colonists could make more profit selling sugar and tobacco to Dutch merchants, these Acts forbade them to sell to anyone but Britain at prices fixed by the British. Colonial merchants resorted to smuggling.

In practice, mercantilism required military force which naturally exacerbated conflicts between competing kingdoms. The persistence by he Dutch to profit from England's North American colonies led to the first Anglo-Dutch War in 1652. Indeed, the American Revolution, in the next time period, can be seen as an attempt by the colonies to gain economic independence from British mercantilistic restrictions.

Competition for the globe's limited resources drove countries to streamline their economic pursuits. Consequently, in the early 1600s European countries developed new methods of financing exploration and business. Since trading ventures were too expensive for most individuals to fund, investors began to pool their resources together into organizations called joint-stock companies. The most famous of these, the British East India Company (EIC), began in 1600 when the British government gave 218 London investors a royal monopoly of all trade east of the Cape of Good Hope. Established about one year later was the Dutch East India Company, known

as the VOC. They were initially a much larger and wealthier rival of the EIC, with 10 times the capital resources of its British counterpart. Joint-stock companies proliferated. The Dutch West Indies Company traded in the New World and founded New Amsterdam, today New York City. And the Virginia Company of London was given a monopoly on the mid-Atlantic coast of North America.

Joint-stock companies were an improvement over traditional partnerships because of something called limited liability. In a partnership, investors pool their resources together and share the profits or losses collectively. In the case of a shipwreck or some other calamity, however, investors would owe more than they put in and could be driven to bankruptcy. But the limited liability of a joint-stock company meant that an investor could never lose more than what he paid in. With risks thus limited but the potential for profit still high, joint-stock companies attracted thousands of investors willing to put up money, called stock, in these ventures.

Voyages funded by joint-stock companies were more efficient and profitable than those funded by monarchs. Unconcerned with religious conversion, their voyages were streamlined to produce as much profit as possible in order to please investors and attract more capital. Thus countries such as Spain and Portugal, in which the king financed business, could not compete with the more efficient business practices of companies. Spain endured only as long as it could drain the New World of its silver reserves.

Since the classical age several major trade routes dominated trans-regional trade. Political, environmental and demographic changes altered the ebb of flow in the volume of trade and gave each a turn at being the dominant trade route. These major routes coexisted for most of this time and no major new networks were added. Between 1450 and 1750, however, an entirely new trade route emerged and became the world's dominant network of exchange. The Atlantic System connected the old and new worlds in a triangular pattern across the ocean. A truly global system of trade was established.

In an effort to make trade as efficient as possible, ships in this triangular pattern never sailed empty. From Africa, they sailed across the Atlantic to the New World with slaves. After selling the slaves, they sailed to Europe with sugar, tobacco, and rum. After loading their ships with alcohol, metal items, and guns, they said to Africa's west coast to trade these things for slaves and begin the circuit all over again.

We saw in the previous period (600-1450) that the creation of a common currency in China facilitated trade in that region. Widely accepted currencies speed up transactions and provide standardized way for merchants to measure the value of commodities. In this period the use of a common currency expanded from regional to global use. The Spanish peso de ocho, or "piece of eight," was the first currency in history to be used globally.

This currency was the product of Spain's mining of enormous amounts of silver in the New World. In present day Bolivia and Mexico, they discovered massive deposits of silver, including a mountain full of silver at Potosi. After the purest veins of silver were quickly strip-mined production slowed; then the

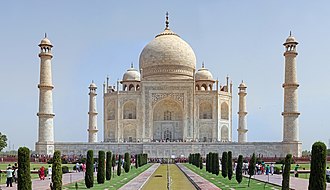

Spanish introduced the amalgamation method of using mercury to extract silver from ore. Production soared. In two centuries the silver mines of the Spanish New World produced 40,000 tons of silver. [1] The industrial centers that grew around these mines minted 2.5 million silver coins per year. The peso de ocho, worth about 80 US dollars today, gained acceptance around the world and lubricated global trade on an unprecedented level. Mughal India wanted Spanish silver for payment for its pepper sales, and this surge of silver funded Shah Jahan's construction of the Taj Mahal. Much of the Spanish silver ended up the hands of the Chinese, who had no desire for European products but readily accepted silver as payment for its coveted exports. The peso do ocho was even accepted currency in the United States until the Coinage Act of 1857. [2]

In this time period peasant labor increased. Powerful states made use of peasants for their economic and political prerogatives. To secure the new frontier settlements to the east that had growing since Ivan IV, Russian Czars encouraged peasants to migrate to Siberia. They were provided with incentives, such as grain, seeds, and farming tools. Many peasants sought to create a better and more independent life for themselves by moving east.

Fur trappers pushed to the east as well to take advantage in the profitable trade in furs. For the most part, however, the eastern frontier was settled by peasants who were encouraged to migrate by the Russian government.

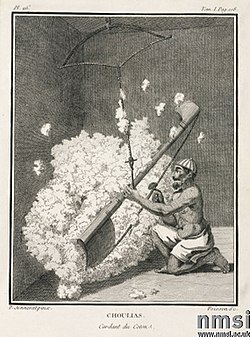

During the Mughal empire, the price of spices declined. To maintain their profits, joint-stock companies such as the British East India Company and the Dutch VOC encouraged Mughal leaders to supplement pepper exports with cotton textiles. Cotton, which was softer than many fabrics and could be dyed and printed with elaborate patterns, became an extremely popular fad in Europe. To meet this demand, the Mughal government forced a vast number of peasants to work cotton fields and textile operations. As in Russia, state mandates and incentives led to the mass mobilization of peasants to aid state objectives.

The Qing (Manchu) Empire likewise utilized peasants for their economic gain. Even though they focused China’s economic strength more on the practice of agriculture than commerce, silk exports became important to their economy. The city of Canton in the south of China was the only location where Europeans were allowed to conduct business and the Chinese accepted only gold and silver as payment for their exports. To meet the demand of foreigners for silk, the government forced peasants to work in the growing of mulberry plants (necessary for silk worms to produce quality silk) and in the general production of silk. In some areas, silk production exceeded rice production and consumed all surplus labor of peasant families. [3]

Despite all the dramatic changes in labor during this period, Africa continued to supply slaves to the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean as it did in previous periods. Records of the slave trade in Africa date back to 2900 B.C.E. when slaves were transported from Sub-Saharan Africa to Nubia. [4] As the slave trade grew tremendously in the Atlantic system to supply plantation labor in the Americas, the movement of African slaves to the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean regions was an important continuity with the past.

The Portuguese colony of Brazil was the first to implement the plantation system in the New World. A plantation is a large commercial farm used to grow a single cash crop for export. First tobacco, and then sugar became the most lucrative crops in this system. But indigenous labor did not work well as many native Americans succumbed to diseases carried by the European plantation managers. Europeans looked to Africa. With the growth of the plantation system the demand for African slaves increased. Over 10 million were transported across the Middle Passage of the Atlantic System.

In addition to the rise of new elites and the fluctuating power of intermediaries, this era saw demographic, gender, and family changes as well. In Africa, the slave trade caused a significant demographic change. Between 1500 and 1900 approximately 10 million slaves were taken from Africa's west coast to labor in the Americas. During that same time, 6 million left the east coast as slaves in Asia and 8 million were enslaved within the African continent. [5] The result was that just as European and Asian populations were increasing due to the transferring of new crops (The Columbian Exchange), Africa saw a significant decline in population. Moreover, since there was an emphasis placed on having male slaves for sugar plantations in the Americas, the drain of slaves on the west African coast had a strong gender dimension. Places hit hardest by the slave trade, such as Angola, experienced a catastrophic gender imbalance with females comprising up to 65 percent of the population. [6]

The increase in interactions between newly connected hemispheres and intensification of connections within hemispheres expanded the spread and reform of existing religions and created syncretic belief systems and practices.

Islam blended with local cultures in Southeast Asia as well. The prophet Mohammed showed up as a character in Hindu epics and local folklore. [8] In Indonesia, the selamatan, a local feast of reconciliation, was used by Muslim leaders to convert people to the new faith. Conversion stories took on traditional characteristics, such as accompanying miracles and signs. In Javanese culture, these miracles were necessary to establish the leader as a channel of communication between God and people. [9] As the Islamic Mughal Dynasty formed in South Asia, an enormous amount of religious syncretism formed. A new world religion, Sikhism, combined Islam's notion of the oneness of God with the Hindu concept of inclusiveness. Although it did not endure, Akbar attempted to create a new faith by combining elements of Hinduism, Islam, Christianity and Zoroastrianism. In the arts, Persian, Hindu and Muslim styles blended to form a distinctively Mughal form of painting.

A major force in the spread of Islam during this era was Sufism. This sect of Islam emphasized the experiential and mystical approach to God over formal practices and creeds. Sufis sought emotional encounters that brought them into union with God. Organized into Orders, each group had is own habits and rules and usually formed around a charismatic holy man. Sufism served to spread Islam in two ways; because they begged for food and did not own homes, Sufis were wandering mystics and became de fact missionaries. Secondly, their emphasis on experience rather than doctrines allowed them to adapt to many host cultures and form syncretic belief systems. [10] In Southeast Asia, for example, Sufis were accepted by the Hindu Bhaktis who had their own tradition of experiential religion. Thus Sufism was absorbed into a wider devotional movement that transcended religious faiths. [11] In West Africa, where Sufi Orders became important institution in African society, Sufism became an essential element of Islam's spread and integration. In these Orders, Sunni and Shia Muslims, heretics, and traditional spiritualists all came together. Sufi mystics were often well versed in Islam as well as in the spiritual ways of traditional

Christianity In this era Christianity became more diversified and spread across the globe. The impetus for these changes began in Western Europe where the unity of Christian civilization was shattered by the Protestant Reformation. The printing press made the Bible available to countless Christians, and many of them took it to be a higher authority in their lives than the Pope and hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church. Believers who "protested" the church and broke from Catholicism became known as Protestants. Owing to their belief that Christians can read and interpret the Bible for themselves, Protestants quickly splintered into many subgroups based on varying interpretations and practices. The Protestant Reformation quickly became political as some European monarchs left the Catholic Church only to free themselves from the Pope's authority and become more autonomous.

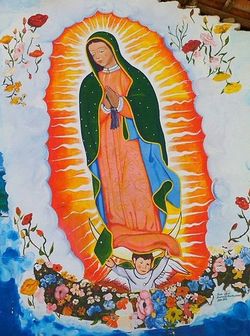

Syncretism in the Americas The spread of religion in this era led to rich syncretic blends of religious symbolism and beliefs. We have already mentioned the development of Sikhism above. In the Americas, the Jesuits and other Catholic missionaries were often disappointed with their attempts to spread their faith to the Amerindians who imbued Christian symbols with their own traditional beliefs. The best example of this blending is the cult of the Virgin of Guadalupe, the patron saint of Mexico today. In 1531 a peasant reported seeing a vision of the Virgin Mary to his local priest. The site of this apparition was a hill used to worship the Aztec fertility god Tonantzin in pre-Columbian times. The Spanish had previously destroyed the temple to Tonantzin on this very hill and replaced it with a Catholic church, a common practice in the conquest of Mexico. According to reports, when an image of this vision was first unveiled at this church peasants did not recognize it as the Virgin Mary but instead shouted "Tonantzin! Tonantzin!" [16] One of the Aztec titles for Tonantzin was "Seven Flowers," [17] an interesting fact when we see that the Virgin of Guadalupe is frequently depicted amidst an abundance of flowers. Thus in Latin America is it less accurate to speak of "conversion" than of the rise of a genuinely mestizo religion in which indigenous people projected ancient forms of worship onto the symbols of the new Catholic faith. [18]

A similar process occurred in the Caribbean. The indigenous population of Haiti (Hispaniola) was almost entirely wiped out by disease and conquest and replaced by French Catholics and African slaves. Ironically, Catholic authorities in Haiti accelerated the process of syncretism by forbidding slaves from worshipping their former African deities. Slaves adapted by using Catholic saints as representatives of their closest African counterparts. In worshiping the Virgin Mary, Africans were actually worshiping Oshun, the beautiful Nigerian water goddess of love. They continued their worship of Legba, the god who holds to keys to the underworld and decides people's eternal destiny, by paying their respects to Saint Peter. [19] By appropriating Catholic saints and images to their own beliefs, slaves in Haiti could use them as "a veil behind which they could practice their African religions." [20] The resulting syncretic religion that came out of this practice is known as Vodun. Although often misunderstood in popular culture (sometimes called Voodoo), it is a rich and varied belief system containing a system of justice, folk medical practices, oral and artistic traditions, and creeds. The religion of Santeria in Cuba developed similarly by blending the beliefs of Yoruba slaves with Spanish Catholicism.

- ↑ Silver, Trade, and War: Spain and America in the Making of Early Modern Europe, (2000), Stanley J. Stein, Barbara H. Stein, p. 21.

- ↑ http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llsl&fileName=011/llsl011.db&recNum=184

- ↑ Peasants and Revolution in Rural China: Rural Political Change in the North China Plain and the Yangzi Delta, 1850-1949 (2007) Chang Liu, p.116.

- ↑ A History of Sub-Saharan Africa (2007) Robert O. Collins, James M. Burns, p.228.

- ↑ The Atlantic Slave Trade: Effects on Economies, Societies and Peoples in Africa, the Americas, and Europe, (1992), Joseph E. Inikori, p. 119-20.

- ↑ The Atlantic Slave Trade, (1992), Inikori, p. 120.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. (2009), Ga ́bor A ́goston, Bruce Alan Masters, p. 216.

- ↑ Islam in South Asia in Practice. (2009),Barbara Metcalf, p. 104.

- ↑ Islam in South Asia in Practice, p. 105.

- ↑ The Spread of Islam: The Contributing Factors, (2002) Abū al-Faz̤l ʻIzzatī, A. Ezzati, p. 164.

- ↑ Islam in South Asia in Practice, p. 93, 105.

- ↑ The Spread of Islam: The Contributing Factors, p. 164.

- ↑ The Islamic World. (2013), Andrew Rippin, p. 27.

- ↑ The History of the Church in Latin America. (1981), Enrique Dussel, p. 59.

- ↑ The History of the Church in Latin America, p. 60.

- ↑ The Virgin of Guadalupe: Theological Reflections of an Anglo-Luthern Liturgist. (2002), Maxwell E Johnson, p. 57.

- ↑ https://www.princeton.edu/~achaney/tmve/wiki100k/docs/Tonantzin.html

- ↑ Our Lady of Guadalupe: The Origins and Sources of a Mexican National Symbol, 1531-1797 (1995), Stafford Poole, p. 79.

- ↑ Sacred Possessions: Vodou, Santeria, Obeah, and the Caribbean (1997), Margarite Fernández Olmos, Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert, p. 5.

- ↑ Cited in Sacred Possessions: Vodou, Santeria, Obeah, and the Caribbean (1997), p. 5.