Topic 4.3 The Columbian Exchange

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

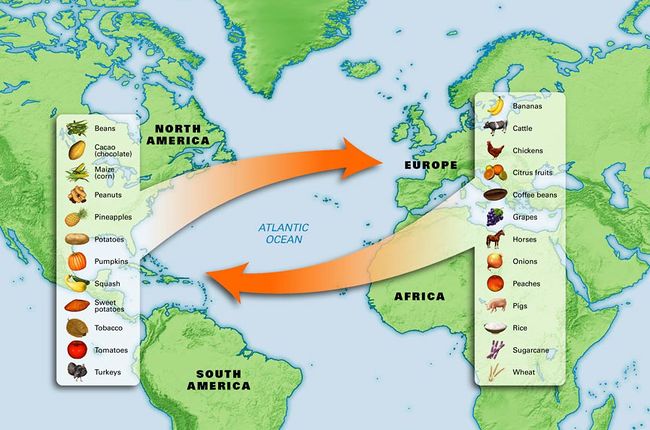

The new connections between the Eastern and Western hemispheres resulted in the Columbian Exchange.

- After the voyage of Columbus, the two halves of the planet learned that each other existed. As networks of trade and communication expanded to include both hemispheres, items from one side made their way over to the other side in a process of exchanges that lasted several centuries. In the 20th century a historian named this process of intentional and unintentional sharing the Columbian Exchange. [1] This sharing of items took place most predominately in the following categories:

- A significant part of the exchanges that took place after Columbus was biological in nature. Because of their long history of contact with farm animals, Europeans were carrying microorganisms to which they had developed immunities. The native Americans did not have these immunities and were thus highly susceptible to the diseases caused by the microorganisms. [2] New encounters between Europeans and native Americans caused the spread of viruses such as measles and small pox with catastrophic results. Natives died by the millions. In central Mexico, pandemic diseases killed 60 to 90 percent of the population. When the Tlaxcalan people sided with the Spaniards against the Aztecs, Tlaxcala paid a heavy price. The disease they caught from their Spanish allies killed up to 1,000 of them daily, with a total of about 150,000 deaths. [3] In addition to smallpox and measles, Europeans also inadvertently spread cholera, malaria, influenza, and bubonic plague in the New World. The decimation of native Americans due to these diseases played a large role in the Spanish conquest of the mighty Incan and Aztec empires. [4]

- A significant part of the exchanges that took place after Columbus was biological in nature. Because of their long history of contact with farm animals, Europeans were carrying microorganisms to which they had developed immunities. The native Americans did not have these immunities and were thus highly susceptible to the diseases caused by the microorganisms. [2] New encounters between Europeans and native Americans caused the spread of viruses such as measles and small pox with catastrophic results. Natives died by the millions. In central Mexico, pandemic diseases killed 60 to 90 percent of the population. When the Tlaxcalan people sided with the Spaniards against the Aztecs, Tlaxcala paid a heavy price. The disease they caught from their Spanish allies killed up to 1,000 of them daily, with a total of about 150,000 deaths. [3] In addition to smallpox and measles, Europeans also inadvertently spread cholera, malaria, influenza, and bubonic plague in the New World. The decimation of native Americans due to these diseases played a large role in the Spanish conquest of the mighty Incan and Aztec empires. [4]

- The Columbian Exchange also diffused new crops from the Americas to locations throughout the world. Potatoes were transplanted to places like Europe, Russia, and China. Because they produce heavier yields than cereal grains and can be cultivated in higher altitudes, potatoes led to increased surpluses of food. About 25% of the population growth in Afro-Eurasia between 1700 and 1900 can be attributed to the cultivation of potatoes. [5] China, for example, experienced a rapid population growth after potatoes were widely cultivated there. Tomatoes and hot chili peppers were also transplanted from their place of origin in South America to Afro-Eurasia. Today, the cuisines we characteristically associate with Italy and Asia are unthinkable without tomatoes and hot peppers, respectively.

- Some New World plants were cultivated as cash crops and exported to the Old World. The Europeans learned about tobacco from the Native Americans. Although the natives did not use it recreationally, its use became widely popular with Europeans in the New World and back home. In the English colony of Jamestown, tobacco leaves were used as currency and the exporting of tobacco as a cash crop is credited with having saved colonial Virginia from ruin. [6] A more important cash crop than tobacco was sugar. Indigenous to Southeast Asia, sugarcane was brought to the Caribbean by the Spanish early on. The demand for sugar in Europe grew, as it was a more convenient and potent sweetener than what was available to them. The Portuguese introduced the plantation system in Brazil to grow sugarcane. Then in the early 17th century a discovery was made that dramatically increased the cultivation of sugar. Plantation slaves discovered that molasses, a byproduct of the production of sugar that was often discarded, could be distilled into alcohol. [7] This new product, Rum, meant that sugarcane could produce two highly profitable products and had virtually no waste. Entire forests were cleared to grow sugarcane and the plantation system proliferated across the Caribbean. This in turn created a tremendous demand for slaves. The cash crop of sugar--and to a lesser extent tobacco--increased the slave trade of the Atlantic system.

- Some New World plants were cultivated as cash crops and exported to the Old World. The Europeans learned about tobacco from the Native Americans. Although the natives did not use it recreationally, its use became widely popular with Europeans in the New World and back home. In the English colony of Jamestown, tobacco leaves were used as currency and the exporting of tobacco as a cash crop is credited with having saved colonial Virginia from ruin. [6] A more important cash crop than tobacco was sugar. Indigenous to Southeast Asia, sugarcane was brought to the Caribbean by the Spanish early on. The demand for sugar in Europe grew, as it was a more convenient and potent sweetener than what was available to them. The Portuguese introduced the plantation system in Brazil to grow sugarcane. Then in the early 17th century a discovery was made that dramatically increased the cultivation of sugar. Plantation slaves discovered that molasses, a byproduct of the production of sugar that was often discarded, could be distilled into alcohol. [7] This new product, Rum, meant that sugarcane could produce two highly profitable products and had virtually no waste. Entire forests were cleared to grow sugarcane and the plantation system proliferated across the Caribbean. This in turn created a tremendous demand for slaves. The cash crop of sugar--and to a lesser extent tobacco--increased the slave trade of the Atlantic system.

- Another aspect of the Columbian Exchange was the introduction of Old World domesticated animals to the New. Europeans brought pigs, cows, sheep and cattle to the Americas as well as rodents like rabbits and rats. With wide open spaces and virtually no natural predators, these animals quickly multiplied across the Americas; by 1700, herds of wild cattle and horses in South America reached 50 million. [8] In North America, tribes like the Navajo became sheepherders and began to produce woolen textiles. The abundance of cattle increased the amount of meat in New World diets and provided them with hides. The introduction of horses had an even greater effect. They dramatically increased the efficiency of hunters and warriors, and tribes like the Comanche, Apache, Blackfoot and Sioux grained greater success in hunting the buffalo herds on the plains of North America. [9] Along side these animals brought by Europeans, slaves brought new plants to the New World such as yams, okra, and black-eyed peas. Soon they became common foods that took the place of most indigenous crops, except maize (corn).

- Another aspect of the Columbian Exchange was the introduction of Old World domesticated animals to the New. Europeans brought pigs, cows, sheep and cattle to the Americas as well as rodents like rabbits and rats. With wide open spaces and virtually no natural predators, these animals quickly multiplied across the Americas; by 1700, herds of wild cattle and horses in South America reached 50 million. [8] In North America, tribes like the Navajo became sheepherders and began to produce woolen textiles. The abundance of cattle increased the amount of meat in New World diets and provided them with hides. The introduction of horses had an even greater effect. They dramatically increased the efficiency of hunters and warriors, and tribes like the Comanche, Apache, Blackfoot and Sioux grained greater success in hunting the buffalo herds on the plains of North America. [9] Along side these animals brought by Europeans, slaves brought new plants to the New World such as yams, okra, and black-eyed peas. Soon they became common foods that took the place of most indigenous crops, except maize (corn).

- New World crops that were transplanted to Afro-Eurasia improved the variety and nutritional content of the population. The coming of potatoes, sweet potatoes, and maize to the Old World "resulted in caloric and nutritional improvements over previously existing staples." [10] Tomatoes and peppers not only added vitamins and improved the taste of Old World diets; they contributed to the development of regional cuisines.

- New World food crops made different demands on the soil than crops that had been cultivated for centuries in the Old World. Fields whose fertility had declined with tireless planting of traditional crops were given new life when New World crops arrived. The new crops also had different growing and harvest times. Thus New World crops complimented crops already grown in the Old World creating more varied, nutritional, and abundant food production. [11]

- New World crops that were transplanted to Afro-Eurasia improved the variety and nutritional content of the population. The coming of potatoes, sweet potatoes, and maize to the Old World "resulted in caloric and nutritional improvements over previously existing staples." [10] Tomatoes and peppers not only added vitamins and improved the taste of Old World diets; they contributed to the development of regional cuisines.

- The presence of the Europeans had negative effects on the environment of the New World. Now that trade was global, there was an urgent need for a larger number of ships. Easily accessible forests in Europe had long since disappeared, so Europeans looked to the seemingly unlimited timber of the New World for their shipbuilding needs. Further contributing to this deforestation was the single cash-crop nature of the plantation system. Tremendous profits could be made by converting huge tracks of land to sugar or tobacco production. This required clear cutting forests which led to increased erosion and flooding.

- The presence of the Europeans had negative effects on the environment of the New World. Now that trade was global, there was an urgent need for a larger number of ships. Easily accessible forests in Europe had long since disappeared, so Europeans looked to the seemingly unlimited timber of the New World for their shipbuilding needs. Further contributing to this deforestation was the single cash-crop nature of the plantation system. Tremendous profits could be made by converting huge tracks of land to sugar or tobacco production. This required clear cutting forests which led to increased erosion and flooding.

- Deforestation allowed cattle and pigs, which Europeans had brought to the New World, to proliferate tremendously. Unhindered by thick forests, livestock was free to roam and scavenge. They destroyed native farms, eating harvests and trampling crops. Europeans who practiced subsistence farming also had a negative effect on the environment. Instead of rotating crops, as they did in Europe where land was scarce, they practiced slash-and-burn agriculture in the New World where land was abundant.

- Deforestation allowed cattle and pigs, which Europeans had brought to the New World, to proliferate tremendously. Unhindered by thick forests, livestock was free to roam and scavenge. They destroyed native farms, eating harvests and trampling crops. Europeans who practiced subsistence farming also had a negative effect on the environment. Instead of rotating crops, as they did in Europe where land was scarce, they practiced slash-and-burn agriculture in the New World where land was abundant.

- ↑ The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492, (1972), Alfred W. Crosby.

- ↑ Disease and Medicine in World History, (2003), Sheldon J. Watts, p. 27.

- ↑ Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492-1650, (1998), Nobel David Cook, pp. 101-102.

- ↑ The Last Days of the Incas, (2007), Kim MacQuarrie, pp. 47-8.

- ↑ The Potato's Contribution to Population and Urbanization: Evidence from a Historical Experiment. "Quarterly Journal of Economics," 126 (2), Nunn, Nathan; Qian, Nancy (2011), pp.593–650.

- ↑ The Relentless Revolution: A History of Capitalism, (2010), Joyce Appleby, p. 131.

- ↑ The Complete Book of Spirits : A Guide to Their History, Production, and Enjoyment. (2004), Anthony Dias Blue, p. 70.

- ↑ The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History Volume 1: To 1550 Brief. (2010, 5th ed.), Pamela Kyle Crossley, Daniel R. Headrick, Steven W. Hirsch, Lyman L. Johnson, p. 375.

- ↑ The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History Volume 1: To 1550 Brief. (2010), Crossley, et al., p. 376.

- ↑ The Columbian Exchange: A History of Disease, Food and Ideas, "Journal of Economic Perspectives," 24 (2), Nunn, Nathan; Qian, Nancy (2010), 163-188, p. 167. http://www.econ.yale.edu/~nq3/NANCYS_Yale_Website/resources/papers/NunnQianJEP.pdf

- ↑ The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492. (2003), Alfred W. Crosby, p. 177.