Topic 2.1 The Silk Roads

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

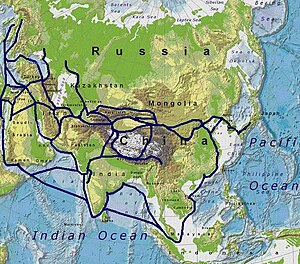

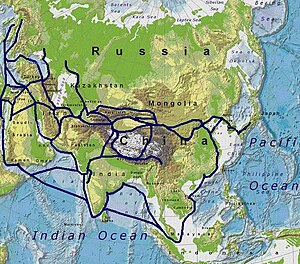

Note the Silk Roads connected every classical civilization. Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Silkroutes.jpg

The Jade Gate. Trade between China and the central Asian nomads took place at this passage in the Great Wall. Photo Credit: John Hill

The Silk Roads were made up of an indirect chain of separate transactions through which goods crossed the entire land area of Eurasia. Rarely did merchants themselves travel the length of these routes; in fact, few of them knew the complexity and breadth of the Silk Roads. Merchants primarily engaged in local instances of "relay trade" in which goods changed "hands many times before reaching their final destinations."[1] Because the Silk Roads crossed land it was much more expensive and dangerous to move goods. Consequently, trade focused on luxury items that would bring a nice profit making the greater risks worthwhile. Particularly important were luxury items with a high value to weight ratio.

- The volume of trade increased dramatically as the classical empires formed. The Romans, Gupta, and Han were centers of production and huge markets for goods. Moreover, the laws and legal systems of these empires provided security for merchants, encouraging them to take more risks. As always, the primary items of trade were luxury goods, and nomadic people continued to play an important role; their movements sometimes served as important connections between segments of trade, buying in one place and selling in another. Some nomads became settled people and made their living off of trade. Nevertheless, the volume of trade on the Silk Roads was connected to the strength of the classical civilizations during this period and declined when they fell into ruin.

- The volume of trade increased dramatically as the classical empires formed. The Romans, Gupta, and Han were centers of production and huge markets for goods. Moreover, the laws and legal systems of these empires provided security for merchants, encouraging them to take more risks. As always, the primary items of trade were luxury goods, and nomadic people continued to play an important role; their movements sometimes served as important connections between segments of trade, buying in one place and selling in another. Some nomads became settled people and made their living off of trade. Nevertheless, the volume of trade on the Silk Roads was connected to the strength of the classical civilizations during this period and declined when they fell into ruin.

- The Silk Roads had their origins in Asia as nomadic and settled people exchanged goods. In part, it began because of environmental conditions. The soil in China lacks selenium, a deficiency that contributes to muscular weakness, low fertility, and reduced growth in horses.[2] Consequently, Chinese-raised horses were too frail to support a mounted soldier rendering the Chinese military weak in the face of the powerful cavalries of the steppe nomads. [3] Chinese emperors needed the superior horses that pastoral nomads bred on the steppes, and nomads desired things only agricultural societies could produce, such as grain, alcohol and silk. Even after the construction of the Great Wall, nomads gathered at the gates of the wall to exchange items. Soldiers sent to guard the wall were often paid in bolts of silk which they traded with the nomads.[4] Silk was so wide spread it eventually became a currency of exchange in Central Asia.

- The Silk Roads had their origins in Asia as nomadic and settled people exchanged goods. In part, it began because of environmental conditions. The soil in China lacks selenium, a deficiency that contributes to muscular weakness, low fertility, and reduced growth in horses.[2] Consequently, Chinese-raised horses were too frail to support a mounted soldier rendering the Chinese military weak in the face of the powerful cavalries of the steppe nomads. [3] Chinese emperors needed the superior horses that pastoral nomads bred on the steppes, and nomads desired things only agricultural societies could produce, such as grain, alcohol and silk. Even after the construction of the Great Wall, nomads gathered at the gates of the wall to exchange items. Soldiers sent to guard the wall were often paid in bolts of silk which they traded with the nomads.[4] Silk was so wide spread it eventually became a currency of exchange in Central Asia.

- In the period 1200 to 1450, the Silk Roads continued to focus on luxury items such as silk and other items whose weight to value ratio was low. In the post-classical age, however, the Silk Roads diffused important technologies such as paper-making and gunpowder. Continuing a phenomenon from the classical age, they would also spread disease; the Black Death would spread from Asia to Western Europe along Silk Road and maritime routes eventually killing about one third of the people there. Despite these continuities, the Silk Road network would be transformed by cultural, technological and political developments. By 600 C.E., the classical empires of China, India and Rome had all crashed. Silk Road trade declined with them. The rise of the Islamic Abbasid Caliphate would invigorate trade along the Silk Roads once again. Sharia law, which gave protection to merchants, was established across the Dar al-Islam. Indian, Armenian, Christian and Jewish merchants alike took advantage of Muslim legal protection.[5] Courts and Islamic jurists called qadis presided over legal and trade disputes. All of this enabled trade by decreasing the risks associated with commerce. A more important boost to Silk Road trade in this era was the rise of the Mongol Empire. The Mongols defeated the Abbasid Caliphate in 1258 and the vast Pax Mongolica soon placed the majority of the Silk Roads under one administrative empire. Merchants were more likely to experience safe travel.[6] The Mongol code of law, known as the Yassa, imposed strict punishments on those disturbing trade.[7] The rule of the Mongols in central Asia coincided with the peak of Silk Road trade between 1200 and 1450 C.E..

- In the period 1200 to 1450, the Silk Roads continued to focus on luxury items such as silk and other items whose weight to value ratio was low. In the post-classical age, however, the Silk Roads diffused important technologies such as paper-making and gunpowder. Continuing a phenomenon from the classical age, they would also spread disease; the Black Death would spread from Asia to Western Europe along Silk Road and maritime routes eventually killing about one third of the people there. Despite these continuities, the Silk Road network would be transformed by cultural, technological and political developments. By 600 C.E., the classical empires of China, India and Rome had all crashed. Silk Road trade declined with them. The rise of the Islamic Abbasid Caliphate would invigorate trade along the Silk Roads once again. Sharia law, which gave protection to merchants, was established across the Dar al-Islam. Indian, Armenian, Christian and Jewish merchants alike took advantage of Muslim legal protection.[5] Courts and Islamic jurists called qadis presided over legal and trade disputes. All of this enabled trade by decreasing the risks associated with commerce. A more important boost to Silk Road trade in this era was the rise of the Mongol Empire. The Mongols defeated the Abbasid Caliphate in 1258 and the vast Pax Mongolica soon placed the majority of the Silk Roads under one administrative empire. Merchants were more likely to experience safe travel.[6] The Mongol code of law, known as the Yassa, imposed strict punishments on those disturbing trade.[7] The rule of the Mongols in central Asia coincided with the peak of Silk Road trade between 1200 and 1450 C.E..

- Silk was not the only luxury good to travel along the roads bearing its name. Spices comprised an essential element of the trade in luxuries. In fact, the spice saffron actually had a higher value to weight ratio than silk.[8] But in the world of spices, black pepper was king. As early as Roman times, pepper from India had become a household possession of the rich. When the Visgoths threatened Rome in 410 one of the ransom items they demanded was 3000 pounds of pepper from India. [9] With the resurgence of large states and markets, the demand for pepper soared. Pepper helped food taste better, but it was also thought to have medicinal and preservative powers.

A caravan making use of camel saddles. (Source: http://rolfgross.dreamhosters.com/ErmakovCollection/MyCollection.html)

A caravan making use of camel saddles. (Source: http://rolfgross.dreamhosters.com/ErmakovCollection/MyCollection.html)

- Silk

- Innovations in transportation networks also led to increased exchanges in luxury items. Caravan routes crossing central Asia underwent significant changes during this era that enhanced their performance and efficiency. The terrain between China and the western termini of the Silk Roads is some of the most inhospitable on the planet. Sparse water, extreme temperatures, deserts and rugged mountains made this crossing nearly impossible for individual travelers. Moreover, much of this territory was out of the control of most governments. Banditry was rampant. Thus merchants would only trade in lightweight high-profit luxury items that made the risks of the journey worthwhile. Only in caravans travelling familiar routes could a merchant or traveler hope to survive in this environment.

- Innovations in transportation networks also led to increased exchanges in luxury items. Caravan routes crossing central Asia underwent significant changes during this era that enhanced their performance and efficiency. The terrain between China and the western termini of the Silk Roads is some of the most inhospitable on the planet. Sparse water, extreme temperatures, deserts and rugged mountains made this crossing nearly impossible for individual travelers. Moreover, much of this territory was out of the control of most governments. Banditry was rampant. Thus merchants would only trade in lightweight high-profit luxury items that made the risks of the journey worthwhile. Only in caravans travelling familiar routes could a merchant or traveler hope to survive in this environment.

- As the caravan routes became standardized, nomadic people settled at frequent stopping points to offer services to merchants. For a fee, usually silk, they served as local guides or provided food, water and rest. This practice led to the development of fortified inns for weary travelers called caravanserai (from the Persia karavan sara, which means caravan palace). Some people of the Central Asia steppes made their entire livelihood this way, waiting for the next caravan to stop and get refreshed. With the expansion of luxury goods, caravanserai developed into large thriving centers which owed their very existence to caravan traffic. They also expanded their services. "Travelers would also often exchange their beasts of burden, to either obtain fresh, healthy, and rested animals or trade in one type of animal for another more suitable for the next stage of the journey." [10]

- As the caravan routes became standardized, nomadic people settled at frequent stopping points to offer services to merchants. For a fee, usually silk, they served as local guides or provided food, water and rest. This practice led to the development of fortified inns for weary travelers called caravanserai (from the Persia karavan sara, which means caravan palace). Some people of the Central Asia steppes made their entire livelihood this way, waiting for the next caravan to stop and get refreshed. With the expansion of luxury goods, caravanserai developed into large thriving centers which owed their very existence to caravan traffic. They also expanded their services. "Travelers would also often exchange their beasts of burden, to either obtain fresh, healthy, and rested animals or trade in one type of animal for another more suitable for the next stage of the journey." [10]

{{#invoke:Infobox|infobox}}

- Caravanserai, large and small, formed on the Silk Roads at intervals of about 100 miles, the average distance a camel could travel without needing water. [11] This indicates the important role the camel took on as a beast of burden in the harsh environment of Central Asia. Despite its remarkable adaptation to hot arid climates, the camel was useless for trade without a saddle. The humps on a camel's back are soft and non-supportive; one cannot simply throw packs of goods across its back. The "frame and mattress" saddle, probably developed by Arabs, distributed the weight of the cargo evenly across the camel's back allowing a single camel to carry 500 to 1000 pounds of goods. [12] The camel saddle, along with new breeding techniques (see infobox on Animal Husbandry), greatly increased the volume of luxury goods moving across Eurasia.

- Caravanserai, large and small, formed on the Silk Roads at intervals of about 100 miles, the average distance a camel could travel without needing water. [11] This indicates the important role the camel took on as a beast of burden in the harsh environment of Central Asia. Despite its remarkable adaptation to hot arid climates, the camel was useless for trade without a saddle. The humps on a camel's back are soft and non-supportive; one cannot simply throw packs of goods across its back. The "frame and mattress" saddle, probably developed by Arabs, distributed the weight of the cargo evenly across the camel's back allowing a single camel to carry 500 to 1000 pounds of goods. [12] The camel saddle, along with new breeding techniques (see infobox on Animal Husbandry), greatly increased the volume of luxury goods moving across Eurasia.

- Trade in luxury goods was also facilitated by innovations in forms of credit and economic exchange. Between 600 and 1450, China devised a relatively safe method to make large payments across a vast distance. Special documents, called "flying money," allowed merchants to pay for goods or taxes without having to transport coins in bulk. [13] From Arabs, the practice spread to Western Europe where Italian merchants advanced this method into bills of exchange. Merchants used bills of exchange to purchase imported goods without the hazards of carrying an expensive medium of exchange. The bills, which worked like modern checks, required the existence of two established networks, one of bankers and another of merchants. [14] A merchant would place his wealth in the safe keeping of a banking house which would in turn issue a bill of credit that could be used to purchase goods "imported from outside the local economy. The exporter of the goods would then present the bill for payment to his local representative of the banking network." [15] Of course, all of this had to take place within a framework of laws and courts to reduce the risks involved in such transactions.

- Trade in luxury goods was also facilitated by innovations in forms of credit and economic exchange. Between 600 and 1450, China devised a relatively safe method to make large payments across a vast distance. Special documents, called "flying money," allowed merchants to pay for goods or taxes without having to transport coins in bulk. [13] From Arabs, the practice spread to Western Europe where Italian merchants advanced this method into bills of exchange. Merchants used bills of exchange to purchase imported goods without the hazards of carrying an expensive medium of exchange. The bills, which worked like modern checks, required the existence of two established networks, one of bankers and another of merchants. [14] A merchant would place his wealth in the safe keeping of a banking house which would in turn issue a bill of credit that could be used to purchase goods "imported from outside the local economy. The exporter of the goods would then present the bill for payment to his local representative of the banking network." [15] Of course, all of this had to take place within a framework of laws and courts to reduce the risks involved in such transactions.

- Silk and luxury goods were not the only things that moved across the Silk Roads. Merchants became agents of cultural diffusion. The oasis towns that connected segments of trade became nodes of cultural exchange, especially Buddhism. Mahayana Buddhism spread rapidly, leap-frogging from oasis town to oasis town. The process was facilitated by these towns which often built beautiful Buddhist temples to attract Buddhist merchants abroad. Nestorian Christianity also spread across the Silk Roads into China. Not surprisingly, silk took on a sacred meaning in Buddhist and Christian rituals. Merchants also carried disease. The disease epidemics that devastated the classical civilizations were spread across large ecological zones via the Silk Roads.

- Silk and luxury goods were not the only things that moved across the Silk Roads. Merchants became agents of cultural diffusion. The oasis towns that connected segments of trade became nodes of cultural exchange, especially Buddhism. Mahayana Buddhism spread rapidly, leap-frogging from oasis town to oasis town. The process was facilitated by these towns which often built beautiful Buddhist temples to attract Buddhist merchants abroad. Nestorian Christianity also spread across the Silk Roads into China. Not surprisingly, silk took on a sacred meaning in Buddhist and Christian rituals. Merchants also carried disease. The disease epidemics that devastated the classical civilizations were spread across large ecological zones via the Silk Roads.

- ↑ Ways of the World: A Global History, (2009), Robert W. Strayer, p. 219.

- ↑ Selenium in the Environment, (1994), W.T. Frankenberger (ed.), p. 30.

- ↑ City of Heavenly Tranquility: Beijing in the History of China, (2008), Jasper Becker, p. 18.

- ↑ The Silk Roads: A Brief History with Documents, (2012), Xinru Liu, p. 6.

- ↑ Worlds Together, Worlds Apart, (3rd ed., 2011), Robert Tignor, et al., p. 375.

- ↑ Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250-1350, (1989), Janet L. Abu-Lughod , p. 167,177.

- ↑ Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World. , (2004), Jack Weatherford, p. 67.

- ↑ Religions of the Silk Roads: Premodern Patterns of Globalization, (2010), Richard Foltz, p. 12.

- ↑ Premodern Trade in World History, (2008), Robert L. Smith, p. 92.

- ↑ Religions of the Silk Roads: Premodern Patterns of Globalization, (2010), Richard Foltz, p. 11.

- ↑ A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped the World, (2008), William J. Bernstein, p. 58.

- ↑ Ibid, p. 56.

- ↑ History of the Weksel: Bill of Exchange and Promissory Note, Sergii Moshenskyi, (2008), p. 50.

- ↑ Credit and State Theories of Money: The Contributions of A. Mitchell Innes, (2004) L. Randall Wray, p. 197.

- ↑ Ibid.