Topic 1.1 Developments in East Asia 1200 to 1450

Historical Development: Empires, including China's Song Dynasty, practiced continuities, innovations, and diversity in their methods of state building

The success of China’s Song Dynasty was a result of its selective borrowing from China’s imperial past and establishing these continuities with their own innovations. Perhaps the most important political continuity of the Song had its beginning in the aftermath of one of the most chaotic times in China’s history, the tumultuous Period of the Warring States (475–221 BC).

The Period of Warring States ended when the warrior Qin Shi Huang centralized power and destroyed regional opposition. Although it lasted only 14 years, the Qin Dynasty set in place many important aspects of Chinese civilization.

One of the most important things the Qin did was create a bureaucracy. Bureaucrats are employees of the state whose position in society, unlike nobles or aristocrats, does not rest on an independent source of wealth. Members of the bureaucracy only had positions and power as granted by the emperor. Generally speaking, the bureaucrat's high status and wealth is based on his obedience to his superior. Land owning aristocrats, on the other hand, have large estates and personal fortunes to fall back on; they have a vested interest in influencing the government in their personal favor. Aristocrats also tend to make decisions based on what is best for their location, thus becoming a decentralizing force. By assigning bureaucrats to regions, the Qin bypassed the powerful aristocracy and governed through those whose position depended on loyal obedience to the state. Additionally, the practice of Legalism reinforced the bonds of obligation between bureaucrat and superior. In this manner, the bureaucracy became a tool of centralization for China and placed the entire empire under the leadership of the Qin emperor.

As soon as the emperor died, the people revolted and slaughtered many of the remaining Qin officials. Unlike previous eras, Chinese civilization did not regress into chaos for long. The Han dynasty came to power and ruled China for about 400 years, roughly 200 B.C.E. to 200 C.E. The ability of the Han to maintain a strong central government over such a vast area was greatly facilitated by the Qin reforms under Legalism.

Under the leadership of emperor Han Wudi, the Han Dynasty was responsible for some very important innovations that would have a lasting effect on China: the official adoption of Confucianism and the rise of the civil service examinations.

The Han adopted Confucianism because it was the most organized educational network from which they could draw people for the bureaucracy. To make certain new recruits were educated well, they began testing them through a rigorous system of civil service examinations; to be in the Han bureaucracy, one had to demonstrate a mastery of Confucian ideas on these tests. One effect of this was that the Han bureaucracy was filled with people profoundly influenced by Confucian thought. They were taught to model good behavior for those under them and to respect and submit to those in authority over them. Thus Confucianism not only became deeply embedded in Chinese culture, it also came to re-enforce the political bureaucracy by advocating obedience and benevolent rule. A synthesis was forged between China's political structure and a belief system.

Another innovation of the Tang Dynasty was its policy of establishing tributary states. Although earlier Chinese dynasties collected tribute, the practice became more complex and standardized under the Tang. The Chinese tributary system was based on their belief that Chinese civilization was superior to others, but barbarian and non-Chinese people could have access to Chinese ways providing they ceremonially recognized the supremacy of China and paid tribute to the emperor. [1] Thus China could "radiate" its superior civilization to barbarian people around it. In reality, the tributary system was a means for China to control conquered lands that often proved difficult to rule. Chinese dynasties had long tried to project their control over the Korean peninsula; indeed, its long costly war with Korea did much to discredit the Sui Dynasty, the Tang's predecessor. The Tang Dynasty gave its support the the Silla family of Korea to ensure their rule over the entire Korean peninsula, but it cost the Silla their independence. The price China demanded for helping the Silla was that they become a tributary state of the Tang emperor. Each year representatives from Korea traveled to the Chinese capital to purchase their rule with payments of tribute. They returned with Chinese customs, fads, Buddhist writings, clothing fashions, and literature. Through this tributary relationship much Chinese influence made its way into Korea.[2]

- In summary, the recovery of Chinese civilization in the post classical era was made possible by building on classical traditions, such as the Confucian civil service bureaucracy, and fusing them with new administrative practices such as the equal field system and the creation of tributary states.

- In summary, the recovery of Chinese civilization in the post classical era was made possible by building on classical traditions, such as the Confucian civil service bureaucracy, and fusing them with new administrative practices such as the equal field system and the creation of tributary states.

Historical Development: China's Cultural Traditions had a Huge Impact on neighboring States

Sinification (or, to Sinicize) means the assimilation or spread of Chinese culture. During the Tang and Song dynasties, Chinese civilization became so dynamic and powerful that it influenced, or sinicized, several prominent areas around it. It is important to note not only what aspects of Chinese civilization were absorbed in these areas, but also what the limitations of Sinification were in each location.

Korea

Korea’s oldest known kingdom was conquered by emperor Wudi of the Han Dynasty in about 100 B.C.E. beginning the first wave of Sinification. Although the conquest would be short lived, Chinese influence remained. Interestingly, Buddhism became the cultural bridge linking China to Korea, especially as Korean leaders, anticipating Empress Wu, gave state sponsorship to Buddhism. Chinese writing was introduced, despite the difficulties in adapting Chinese characters to the spoken Korean language. One Korean emperor established universities to teach the Confucian classics to Korean youth. Additionally, the Koreans tried to emulate the Chinese style of bureaucracy but they failed to overcome the power of the aristocracy; the land owning nobles were able to thwart the implementation of a bureaucracy they knew would minimize their own power and influence.

During the restoration of Chinese civilization, the Sui dynasty attempted unsuccessfully to reconquer Korea. (Their failed campaign in Korea had much to do with their downfall.) Soon afterward the more powerful Tang Dynasty was able to conquer Korea but they found ruling it a much more difficult affair. Their authority in Korea was challenged by constant revolts. Finally the Tang emperor struck a deal with the Silla kingdom of Korea. They agreed to remove all military forces from Korea if the Silla would become vassals of the Tang dynasty and make regular tribute payments. Even with the Chinese as their overlords, the Koreans learned that this relation with China was very much to their benefit. Emissaries traveling to China with tribute payments returned with gains of greater value borrowed directly from the Chinese court.

Impressed by the organization and economic success of Tang China, Korean leaders sought to emulate Chinese culture in their homeland. Indeed, during this tributary relationship with China an open flow of culture was opened from China to Korea and Sinification in Korea would reach its peak. Korean scholars traveled to China to consult with Confucian scholars; they returned with the latest Chinese books and learning. Chinese innovations, fashions, styles and etiquette made their way into Korea. The elite classes of Koreans became schooled in Confucianism. In fact, besides Buddhism—which became popular among the Korean masses—cultural Sinification occurred primarily among the aristocratic classes. Despite these influences, however, the Koreans never established a functioning bureaucracy and, consequently, aristocratic families retained their hold over politics and society. Thus the Koreans were never able to curb, like the Chinese, the power and influence of the nobles over the government.

Vietnam

Despite its proximity to China, Vietnam has had a distinct social and cultural heritage which instilled within them an independent spirit. As the Han emperors were consolidating their power, the Viets did not wish to have their traditions obliterated by their powerful neighbors to the north. Nevertheless, the Han dynasty conquered Vietnam and pulled them into their bureaucratic structure. Some Sinification occurred despite the tense relations between the two.

During the Tang dynasty the Chinese armies that marched into Vietnam were met with fierce resistance. However, they were soon victorious and set out to assimilate the Viets into Chinese culture. One benefit the Tang derived from their conquest was a quicker ripening form of rice. Once they had adopted this from Vietnam this type of rice became an important feature of the Tangs agricultural and demographic boom.

In contrast to the Koreans, the Viets did not enthusiastically cooperate with their Chinese overlords and scorned many aspects of Chinese civilization. However, they did selectively adopt from the Chinese what they thought could strengthen them. They found the Chinese system of military organization to be very beneficial. The application of Chinese irrigation technology drastically increased agriculture in Vietnam. The population increased.

In spite of these gains, the Viets resisted total Sinification. Of course, mountains and other geographical barriers made it more difficult for the Chinese to maintain a tight control over Vietnam. But the people themselves became the greatest barrier to Sinification. They resented the distain Chinese bureaucrats had for their traditions. Moreover, the peasants never adopted Chinese culture (except for Buddhism) and were quick to rouse against local Chinese rulers. Perhaps the most visible incongruency between Vietnamese culture and Sinification was Confucian patriarchy. Women in Vietnam had higher positions in society relative to many other civilizations and were allowed to freely engage in trade and other independent activities. Thus they chafed at foreign Confucian teachings which would confine them to their homes and total submission to their husbands. This aversion to patriarchy is one reason the Viets were attracted to Buddhism more than any other belief system coming in from China. At any rate, women played a prominent role in revolting against the Chinese on several occasions.

When the Tang dynasty fell into decline, the Viets mounted a massive revolt and won their independence from China. Future Chinese dynasties, as well as the Mongols, would attempt to conquer the Viets, but to no avail. Vietnam would retain its independence until the 19th century when the French incorporated it, at Indo-China, into its colonial empire.

Despite inability of China to hold on to Vietnam, there was a permanent exchange of culture and technology between the two areas. China borrowed the fast ripening rice from the Viets. In return, Buddhism became an enduring and powerful feature of the religious landscape of Vietnam. The irrigation and agricultural practices the Viets borrowed from the Chinese were a benefit as well. And the military technology and practices they learned from the Chinese helped the Viets drive south and extend their control over their adversaries beneath them (into present day Cambodia).

Japan

Of these three areas Japan was unique in that it consciously and intentionally chose to emulate Chinese civilization. Japan was never conquered by the Chinese, but the success of China under the Tang dynasties motivated Japanese emperors to important elements of Chinese civilization for their own gain.

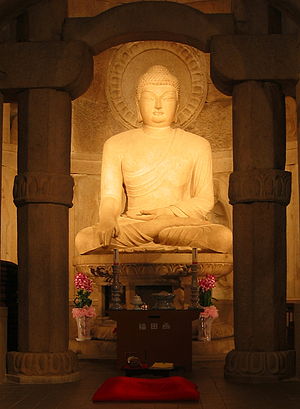

In 646 C.E. the Japanese government embarked upon the Taika reforms, an attempt to reconstruct the Japanese imperial government upon Chinese models. Japanese scholars struggled to master Chinese script and Confucian classics. The Japanese also sought to create a professional bureaucracy with an army made up of peasant soldiers loyal ultimately to the emperor. They introduced the equal-field system of agriculture. Court etiquette mimicked that of the Tang capital. At the popular level, the lower classes converted the Buddhism and combined Mahayana deities with those of their native nature spirits. Chinese influence in Japan was never as profound as it was during the Nara era.

As a result of Sinification Buddhism became so popular that aristocrats feared the power of Buddhists over the government. Their fears were justified when they uncovered a plot by Buddhists to take over the imperial government. A Buddhist had worked his way into he inner social circle of the Emperor’s wife, planned to marry her, depose her husband, and assume control of Japan. Shocked by this foiled plot, the Emperor decided to uproot the Japanese capital at Nara, a haven of Buddhist temples and power, and move it to Heian 28 miles away. The Taika reforms were abandoned and Japan’s great aristocratic families were returned to power in the various provinces.

During the Heian era Japanese courtly life reached a pinnacle of aristocratic and social sophistication. The details of this life are captured in Lady Murasaki’s The Tale of Genji, considered by many to be the first novel in the world. In Genji’s world every day was a pursuit of romantic affairs and artistic entertainments; the drama of social life was attended by elaborate ceremonies and social conventions, each with their proper attire and etiquette. Aristocratic conversation consisted in reciting Japanese verse pertinent to the occasion. According to the novel, one’s social class could be determined by the color of one’s robe, manners, even with the timbre of one’s sneeze. Regardless of one’s place in the complex hierarchy of aristocratic levels, all abhorred the dress, manners and pastimes of the common people. Louis XIV’s court at Versailles would have nothing against the aristocratic refinements and ceremonies of Heian China.

While imperial elites were obsessing about social decorum and romantic intrigue, aristocratic families were busy wrestling control from the imperial bureaucracy. In fact, until the 16th century the emperor and his family would merely be a facade of social pageantry while real power fell in the hands of powerful aristocratic families. The best known of these was the Fujiwara family. By using their wealth and influence over the imperial family (one Fujiwara father saw four of his daughters married to emperors) they basically ruled Japan through their influence at the capital city of Heian. As these families increased their power—often allied with local Buddhism monasteries—they began to deny the resources of their regions to the emperor. With the decrease of imperial control, banditry and crime increased and people began to look to the local families for support rather than the emperor. Powerful families carved out regional kingdoms and political power fragmented in Japan. The Japanese, seeing the Chinese Tang model was no longer relevant to them, abandoned the civil service examinations, the bureaucracy, and the equal field system.

Constant warring between these powerful families led to the establishing of the Shogun, a military dictator who ruled from the imperial capital through the use of local warrior leaders called bushi. By the 15th century, rival claims to the Shogunate let to full scale civil war in Japan. In the fighting, the imperial capital of Heian (Kyoto) was destroyed and the Shogunate was dismantled. Central authority in Japan had now completely fallen and feudalism became the order of the day. Nearly 300 feudal kingdoms emerged protected by samurai loyal to local warlords now called daimyos. Under these leaders, the samurai code of honor (bushido) was increasingly disregarded; warriors turned to sneak attacks, betrayals and less honorable forms of war.

In summary, Japan was the only area around China to intentionally implement aspects of Chinese civilization. Chinese script, bureaucracy, equal field system were all purposely borrowed. Buddhism made its way into Japan as well. The concept of a centralized imperial government, although weakened during this period, would re-emerge later in Japanese history.

Historical Development: China's Song Dynasty Continued to be Highly Commercialized

During this period (600-1450 C.E.) interregional trade in luxury goods began to recover from its decline after the fall of Eurasian classical civilizations. Indeed, the exchange of luxury goods in the post-classical period surpassed that of the Roman/Han era. Luxury goods have important symbolic meanings in societies. As markers of status, they testify to expenditures arising out of surpluses far beyond necessity. [3] Manufactured primarily for external markets, luxury goods bear an association with all things exotic and foreign." [4] Most have rather mundane uses: silver plates and porcelain vases, silk clothing, and spices to enhance food. In these domestic settings luxury goods are "perceived as expressions of taste and civility."

The significant increase in luxury trade was the result of several factors. The creation of Mongol Khanates and the Islamic Caliphates along with the reconstitution of the powerful centralized state in China were certainly major factors.

(The contributions of state formation to the revival in trade is explained in Key Concept 3.2.) In most areas, improved techniques of production, innovations in transportation, and new commercial practices impacted the surge in luxury goods during this period.

During China's Tang Dynasty (618-907) the government standardized the production of porcelain which led to higher quality work and increased quantities. The later Song Dynasty directly benefitted from this. [5] They perfected glazing techniques and mastered the process of regulating, with precise accuracy, the extremely high kiln temperatures necessary for the production of superior porcelain. [6] Production spread from northern China to the south as high quality kaolin clay was discovered there. Japan and Korea would copy Chinese silk production techniques, but no one could match the quality of Chinese porcelain in this period.

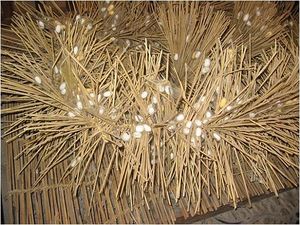

One of the most coveted luxury goods in this period was silk. Although its methods would be duplicated and it would lose its exclusive monopoly of production, China's silk remained the standard of quality throughout this era. During the Sui and Tang dynasties, the state directly oversaw the production of silk and attempted to keep it a state secret. Tang emperors employed silk in the service of the state. They forbade the finest silk from being worn by anyone except the scholar bureaucrats in their administration. The color and pattern of the silk denoted rank and distinguished the bureaucrats from local aristocrats whose influence the government wanted to curb. Only the emperor and his family could wear yellow (for the Byzantines the royal color was purple.) [7] The quantity of silk produced in China, as well as in the Byzantine Empire and other states in Asia, increased tremendously. On the Silk Roads the precious fabric took on symbolic importance, especially in Buddhist monasteries whose interiors were draped with multi-colored silk tapestries donated by patrons. Silk became a de facto currency connecting otherwise disparate civilizations. Below are the basic steps of Chinese silk production:

- ↑ The Ways of the World: A Global History., (2009), Robert W. Strayer, p. 249.

- ↑ Pre-Modern East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Vol 1. (2012) Patricia Buckley Ebrey, p. 108.

- ↑ The Oxford Encyclopedia of Economic History, vol. 2, ed. Joel Mokyr, p. 401.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ http://education.asianart.org/explore-resources/background-information/porcelain-tang-618%E2%80%93906-and-song-960%E2%80%931279-dynasties.

- ↑ China: A New Cultural History, (2013), Zhuoyun Xu.

- ↑ The Silk Roads: A History with Documents, (2012), Xinru Liu, pp. 23-24.