Key Concept 1.3 The Development and Interaction of Early Agricultural, Pastoral and Urban Societies

As agricultural surpluses allowed societies to develop into large urban centers, the foundations for the first civilizations were set. Civilization is not easy to define precisely and can be controversial. Indeed, declaring a group of people "uncivilized" has often been the pretext for conquering them in order to bring them to an alleged higher level of sophistication. Thus the definition of what it means to be "civilized" could be strategically crafted by opportunists and conquerors. Nevertheless, some basic characteristics of civilization can be generalized. First and foremost, civilization implies cities; the word itself is based on the Latin word for civil or city. In addition to cities, civilizations have highly stratified and hierarchical social structures; social and gender equality is not natural to early civilizations. Civilizations also develop states, or governments, organized by bureaucracies and legitimized often by religious belief. Rituals and ceremonies presided over by priests are protected by the state, which in turn gains supernatural support for its laws and decrees. All of these complex institutions, of course, are supported by large agricultural surpluses. Civilizations grew so large and their influence felt so far beyond their borders that it was inevitable that they would have contact with other civilizations and nomadic people. Trade between these people spread ideas, technologies and even diseases. And as the needs of urban centers grew, the struggle for limited resources often led them to military conflict.

- I. Core and foundational civilizations developed in a variety of geographical and environmental settings where agriculture flourished.

The following are known as Core and Foundational civilizations. The first four were located in the valleys of important rivers:

- Mesopotamia

- Egypt

- Indus River Civilizations

- Shang

- Olmecs

- Chavin

You can find an interactive activity to help you learn these locations HERE.

- II. The first states emerged within core civilizations.

- A. The states that emerged in core civilizations welded great power over people's lives and came to reinforce the inequalities that first developed with the advent of agriculture. A state is single political system or government presiding over a group of people or societies. It can be a single city under one leader, or a cluster of cities and communities under a king. It can be a modern democratic nation or a totalitarian regime. States sometimes included people who did not willingly chose to live under their government, as in conquered people living in an empire. What the best form of a state should be and its role in the lives of its people has been debated throughout the history of civilization. Only in recent history have some people come to believe the state's function is to protect their freedoms, guard their property, and create the conditions for the individual to freely flourish as he or she wishes. The individualism inherent in this modern view did not exist in the pre-modern world. Indeed, many of our most cherished beliefs--equality, personal liberty, and tolerance--were not as valued by our ancestors.

- A. The states that emerged in core civilizations welded great power over people's lives and came to reinforce the inequalities that first developed with the advent of agriculture. A state is single political system or government presiding over a group of people or societies. It can be a single city under one leader, or a cluster of cities and communities under a king. It can be a modern democratic nation or a totalitarian regime. States sometimes included people who did not willingly chose to live under their government, as in conquered people living in an empire. What the best form of a state should be and its role in the lives of its people has been debated throughout the history of civilization. Only in recent history have some people come to believe the state's function is to protect their freedoms, guard their property, and create the conditions for the individual to freely flourish as he or she wishes. The individualism inherent in this modern view did not exist in the pre-modern world. Indeed, many of our most cherished beliefs--equality, personal liberty, and tolerance--were not as valued by our ancestors.

- Most creation myths held that the world sprung out of some primordial state of chaos, and to hold this chaos at bay early civilizations stressed the importance of order above freedom. They tolerated hierarchies and inequality to a degree most of us today would find highly distasteful. A hierarchical society, with the leader at the top, the intermediate elites and bureaucrats, and finally the masses of agricultural labors at the base, was thought to be essential to an orderly and secure civilization. This has its literal embodiment in the pyramids of Egypt rising, as it were, from the harsh chaos of the North African desert.

- Most creation myths held that the world sprung out of some primordial state of chaos, and to hold this chaos at bay early civilizations stressed the importance of order above freedom. They tolerated hierarchies and inequality to a degree most of us today would find highly distasteful. A hierarchical society, with the leader at the top, the intermediate elites and bureaucrats, and finally the masses of agricultural labors at the base, was thought to be essential to an orderly and secure civilization. This has its literal embodiment in the pyramids of Egypt rising, as it were, from the harsh chaos of the North African desert.

- These hierarchies as well as the power of the leader were most often sanctioned by religion in the ancient world. A close relationship existed between the power of the state and religious belief. Ancient kings adorned themselves with images of divine approval and performed their duties with a mixture of ceremonial and religious rites. Their decrees, military victories and laws were portrayed as being somehow connected with a higher, spiritual cause. Not until the European Enlightenment would politics be shorn from religion, and both given separate domains in public life.

- B. The earth's natural resources are not distributed equally. Thus it was only natural that some states were better situated geographically to compete with others and become successful. We have seen that the discovery of bronze was a great boost to the production of better tools and weapons; it led to larger agricultural yields and more advanced tools. The problem with bronze, however, was that it was brittle and would sometimes break upon contact with armor, bones or rocks. Soon, man learned to make a superior metal: iron. The production of this metal was more complex than that of bronze. Whereas bronze could be produced on an open fire, such fires were not hot enough to produce iron. Man learned to dramatically increase the temperature of fires by blasting air into the coals. This fed the fire more oxygen than it would get from a normal burn. With such fires, iron could be smelted.

- Iron weapons stayed sharp and easily shattered bronze weapons. Armies brandishing these weapons had a significant advantage over armies using stone or other metals. Because its production required additional technological skills, iron-making skills were kept secret by those who first learned how to make it. But it was iron that allowed for the first major wars of territorial expansion.

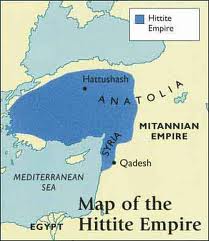

- It was the Hittites who first learned to manufacture iron. The methods of iron production were guarded so carefully the Hittites cut out the tongues of those who knew how to make it in order to prevent this technology from falling into the hands of their enemies. Armed with iron weapons, the Hittites were able to expand their civilization and project their power on surrounding people. Imperial conquest had begun.

- B. The earth's natural resources are not distributed equally. Thus it was only natural that some states were better situated geographically to compete with others and become successful. We have seen that the discovery of bronze was a great boost to the production of better tools and weapons; it led to larger agricultural yields and more advanced tools. The problem with bronze, however, was that it was brittle and would sometimes break upon contact with armor, bones or rocks. Soon, man learned to make a superior metal: iron. The production of this metal was more complex than that of bronze. Whereas bronze could be produced on an open fire, such fires were not hot enough to produce iron. Man learned to dramatically increase the temperature of fires by blasting air into the coals. This fed the fire more oxygen than it would get from a normal burn. With such fires, iron could be smelted.

- C. When powerful cities began to conquer and impose their rule over other communities a new type of political system was born, the empire. Empires grow primarily through military conquest, absorbing land and people into their domain against the will of those conquered. Consequently, empires are likely to be composed of regions with different religious, ethnic, and linguistic traditions. Conquered groups of people rarely accept their foreign domination peacefully. Centrifugal forces threatened empires, creating fault lines between cultural and ethic zones. Thus the diversity inherent in empires presented new challenges in maintaining political and social order in the ancient world. Such states had to devise techniques for holding their vast domains together. See video on the first empires HERE.

- C. When powerful cities began to conquer and impose their rule over other communities a new type of political system was born, the empire. Empires grow primarily through military conquest, absorbing land and people into their domain against the will of those conquered. Consequently, empires are likely to be composed of regions with different religious, ethnic, and linguistic traditions. Conquered groups of people rarely accept their foreign domination peacefully. Centrifugal forces threatened empires, creating fault lines between cultural and ethic zones. Thus the diversity inherent in empires presented new challenges in maintaining political and social order in the ancient world. Such states had to devise techniques for holding their vast domains together. See video on the first empires HERE.

- D. The interaction civilizations had with pastoral nomads often provided the links for the diffusion of new technologies. New weapons and modes of transportation spread from one area to another. As hard as the Hittites tried to conceal their method of iron production, this skill spread to others. When the Assyrians learned iron metallurgy they applied its use more effectively than the Hittites and their army became very feared in the ancient world. In Africa, the Bantu people used iron to facilitate their migration across the continent, spreading this new technology as they moved.

- D. The interaction civilizations had with pastoral nomads often provided the links for the diffusion of new technologies. New weapons and modes of transportation spread from one area to another. As hard as the Hittites tried to conceal their method of iron production, this skill spread to others. When the Assyrians learned iron metallurgy they applied its use more effectively than the Hittites and their army became very feared in the ancient world. In Africa, the Bantu people used iron to facilitate their migration across the continent, spreading this new technology as they moved.

- III. Culture played a significant role in unifying states through laws, language, literature, religion, myths, and monumental building.

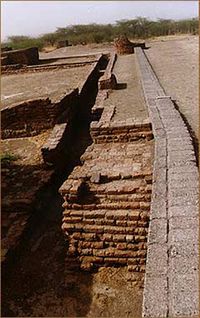

- A. The vast amount of resources civilizations garnered enabled them to fund public and civic projects such as temples, defensive walls, roads, irrigation and sewage systems. Sewage disposal networks have been unearthed at some of the oldest cities. In the city of Lothal in the Indus River valley, a complex sewage system had a main line running through the city with smaller lines connecting to it. Projects of this nature require planning and organization to a degree that can only be carried out by a government. Road construction is another example of the state marshaling resources for projects that advance the good of city. Note that the formation of a large gathering of settled people in one area (a city) necessitated a complex government to organize needed services such as irrigation, sewage systems, and roads.

- Not all public work projects were undertaken for practical urban purposes. The close relationship between the state and religion meant that governments supported the construction of temples and religious monuments. The city-states and empires of Mesopotamia constructed large temples called ziggurats. Religious practice centered around these large buildings, to which people brought offerings of animals, vegetables, fruits and butter. Here priests would offer sacrifices, both human and animal, which were thought to secure the good will of the gods. The ziggurat could perform social and military functions as well. In the temple schools children learned religion, mathematics, geometry and other subjects. Being accessible only by three long sets of stairs, the top of the ziggurat provided safety during times of flooding and invasion.

- A. The vast amount of resources civilizations garnered enabled them to fund public and civic projects such as temples, defensive walls, roads, irrigation and sewage systems. Sewage disposal networks have been unearthed at some of the oldest cities. In the city of Lothal in the Indus River valley, a complex sewage system had a main line running through the city with smaller lines connecting to it. Projects of this nature require planning and organization to a degree that can only be carried out by a government. Road construction is another example of the state marshaling resources for projects that advance the good of city. Note that the formation of a large gathering of settled people in one area (a city) necessitated a complex government to organize needed services such as irrigation, sewage systems, and roads.

- The man hours required to construct a monumental building of this size had to be organized by a central government. To expend so much human labor for this project also testifies to the tremendous surplus of agriculture this civilization could produce. Thus monumental building served to showcase the wealth and power of the state.

- The man hours required to construct a monumental building of this size had to be organized by a central government. To expend so much human labor for this project also testifies to the tremendous surplus of agriculture this civilization could produce. Thus monumental building served to showcase the wealth and power of the state.

- B. These same surpluses allowed civilizations to promote the arts. Human nature seems to have an innate propensity for artistic expression, and we embellish the things we make far beyond what their function or utility alone require. Forms of art give a sense of identity to individuals and groups, just as music and clothing styles still do today. In the earliest civilizations, jewelry making, painting, sculpting and other forms of art were promoted and funded by elites, those possessing the wealth to support labor not inherently necessary for human survival.

- B. These same surpluses allowed civilizations to promote the arts. Human nature seems to have an innate propensity for artistic expression, and we embellish the things we make far beyond what their function or utility alone require. Forms of art give a sense of identity to individuals and groups, just as music and clothing styles still do today. In the earliest civilizations, jewelry making, painting, sculpting and other forms of art were promoted and funded by elites, those possessing the wealth to support labor not inherently necessary for human survival.

- C. As the buying and selling of goods became more involved, people needed a systematic way to remember information. Complex financial exchanges required a means to record quantities, previous agreements, exchange values and contracts. From trade writing was born. The ability to use written symbols to record quantity and meaning is a giant stride in the development of civilization. (See an interesting article on how writing developed HERE). Previously, small communities retained their collective memories and celebrations through oral traditions; legends, lore, and their meanings were memorized and passed on through stories told to the younger generations. This method works well in small agricultural villages, but oral traditions are not sufficient enough to provide large urban populations with a common identity, or social "glue," to hold them together. Writing inaugurated an information revolution in which stories and records could be disseminated much faster and with greater accuracy. What began as a need to keep records of trade paved the way for written laws, precise communication that did not depend on memory, literary traditions, and a treasure trove of written documents that have given historians a window into the past.

- C. As the buying and selling of goods became more involved, people needed a systematic way to remember information. Complex financial exchanges required a means to record quantities, previous agreements, exchange values and contracts. From trade writing was born. The ability to use written symbols to record quantity and meaning is a giant stride in the development of civilization. (See an interesting article on how writing developed HERE). Previously, small communities retained their collective memories and celebrations through oral traditions; legends, lore, and their meanings were memorized and passed on through stories told to the younger generations. This method works well in small agricultural villages, but oral traditions are not sufficient enough to provide large urban populations with a common identity, or social "glue," to hold them together. Writing inaugurated an information revolution in which stories and records could be disseminated much faster and with greater accuracy. What began as a need to keep records of trade paved the way for written laws, precise communication that did not depend on memory, literary traditions, and a treasure trove of written documents that have given historians a window into the past.

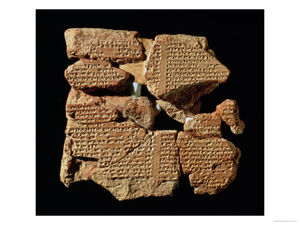

- It seems that the Middle East is where writing began. The Sumerians, in southern Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq), were the first to develop written language, probably around 3500 B.C.E.. Their system of writing, cuneiform, began as literal representations of quantity and pictures. Later these gradually took on abstract characters and became phonetic. After Egypt had contact with Mesopotamia, they too developed a system of writing called hieroglyphs. This written language was only deciphered in modern times when Napoleon discovered the Rosetta Stone during his invasion of Egypt in 1798.

- The dissemination of systems of writing is a perfect example of the interaction of early societies in the ancient world. Writing technology spread into new areas from locations in which it had independently developed. Sometime after writing was discovered by the Sumerians, a group of people called Akkadians migrated into the city-states of Sumer in Mesopotamia. They spoke a Semitic language that would later be called Babylonian, and was related to Hebrew, the language of the ancient Jews. This spoken language was completely different from their Sumerian hosts, but they had no system to record it. Consequently, the Akkadians borrowed the cuneiform writing system from the Sumerians and adapted it to their spoken language. Because cuneiform became phonetic it could be adapted to any spoken language. Soon, eight languages in the ancient world had borrowed cuneiform to record their spoken languages, including Assyrian, Armenian, and Persian.

- Developing later and completely independent from Mesopotamia and Egypt, Chinese writing retained the basic elements of its pictorial characteristics as it evolved. In some instances, a semblance of the original image may still be seen in some Chinese characters. See, for example, the evolution of the Chinese pictograph for a horse below:

- D. Once systems of writing had been developed it became possible for civilizations to create laws and legal codes. Perhaps the best example of an ancient legal code is the Code of Hammurabi developed by the Babylonians. It is not coincidental that the Babylonians were the first to create a codified system of laws. They were one of the earliest empires in history and consequently needed some uniformity and order imposed by a central government over an increasingly diverse population (remember the definition and nature of empires above). Moreover, the Babylonians adopted cuneiform from the Sumerians of Mesopotamia. Cuneiform was more versatile and efficient than pictorial systems of writing, thus allowing for a more literate public. The Code of Hammurabi was created as a way to make the laws known to the population, not only to institute limitations on people's lives but also to protect people from arbitrary rule and give them legal leverage. The preamble to the Code of Hammurabi states that Babylonian (rather then the more academic Sumerian) was to be the language spoken in the courts and in which the laws were written. Because they were inscribed on large black columns across the empire, all people would know what the law required of them.

- One striking feature of the Code of Hammurabi is its strict "eye-for-an-eye" relation between an offense and its punishment. Here, for example, are some excerpts from Hammurabi's Code:

- If a builder build a house for some one, and does not construct it properly, and the house which he built fall in and kill

its owner, then that builder shall be put to death.

- If a builder build a house for some one, and does not construct it properly, and the house which he built fall in and kill

- It seems that the Middle East is where writing began. The Sumerians, in southern Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq), were the first to develop written language, probably around 3500 B.C.E.. Their system of writing, cuneiform, began as literal representations of quantity and pictures. Later these gradually took on abstract characters and became phonetic. After Egypt had contact with Mesopotamia, they too developed a system of writing called hieroglyphs. This written language was only deciphered in modern times when Napoleon discovered the Rosetta Stone during his invasion of Egypt in 1798.

- If it kill the son of the owner the son of that builder shall be put to death.

- If it kill a slave of the owner, then he shall pay slave for slave to the owner of the house.

- More importantly Hammurabi's Code reinforced the social and gender hierarchies of Babylonian civilization. The law imposed different penalties for the same crime committed by people of different social status. The penalty for thief, for example, could be a fine for someone of the upper class and a much harsher penalty, such as dismemberment or death, for someone of the lower class. Thus the inequalities that naturally formed with surpluses of agriculture were standardized and perpetuated in laws that were made known to everyone in the empire. That is not to say that laws were wholly exploitative and unjust. In the Babylonian Empire, a slave had the right to sue his or her master for unfair treatment. We have records for such cases in which slaves won against their masters. The laws of an empire brought uniformity to a new type of political state that was inherently diverse in its ethnic and cultural constitution. The image on the left depicts a stele, or carved stone column, on which the Code of Hammurabi was enscribed. These were placed across the breadth of the empire to disseminate the laws to all people. Note the picture on top of the stele which depicts Hammurabi receiving the laws from the Babylonian sun god Shamash. People are more likely to follow laws if they believe the laws are of divine origin.

- E. This period of early societies and civilizations saw the development of some important seminal religious concepts. Although most of these beliefs cannot be found today in the same form they had in this earlier time, they continue to have a profound influence on billions of religious believers in the modern world. We will see in the next time period how these foundational beliefs developed and became codified into major belief systems during the classical age.

- Vedic period

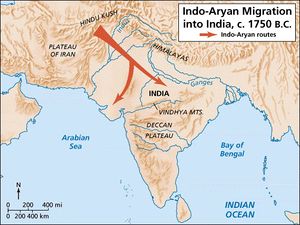

- Around 1500 B.C.E. a group of pastoral nomads know as Aryans began to cross the Hindu Kush mountains into what is today northern India and Pakistan. They brought with them religious hymns, or songs, known as Vedas. For generations priests had memorized these holy poems verbatim and had passed down this wisdom orally. These priests presided over sacrifices of cows and other animals in order to appease their gods, such as Indra, the god of thunder and war. The Vedas told the story of the creation of 4 social groups called varnas into which all people were categorized. Centuries later, Portuguese visitors to India would call these groups castes.

- E. This period of early societies and civilizations saw the development of some important seminal religious concepts. Although most of these beliefs cannot be found today in the same form they had in this earlier time, they continue to have a profound influence on billions of religious believers in the modern world. We will see in the next time period how these foundational beliefs developed and became codified into major belief systems during the classical age.

- Gradually, these nomadic people began to settle down, practice agriculture, and integrate with the indigenous people living in South Asia. Iron tools helped them produce large surpluses of agriculture. As they abandoned their nomadic lifestyles and became more urban, the sacrificial system outlined in the Vedas began to seem less relevant. Holy men who lived outside of towns and villages practiced aestheticism and drew followers, or disciples. These teachers were outside the official religious practices and focused more on philosophical issues, such as the meaning of life and what man's place in the universe is. The teachings of these holy men formed the basis of a body of teachings called the Upanishads and they mark the end of the Vedic period. The core of the Upanishads, the teachings about karma, atman, and reincarnation, would be integral to the formation of Hinduism in the classical age.

- Hebrew Monotheism

- The Hebrews were Semitic people who migrated from Mesopotamia. According to Genesis chapter 12 in the Hebrew scriptures, God made a covenant with Abraham and led him out of his city to a land promised to all his descendants. The Hebrews held to monotheism, a belief in only one supreme God who presided over all the cosmos.

- Monotheism is not just polytheism stripped down to one God. Its belief in a single deity means that all other gods are necessarily false, a position that implies an exclusive claim to religious knowledge. This influence of Hebrew monotheism can be see in Christianity and Islam which developed centuries later. Monotheism also has a strong ethical dimension. The gods of polytheism usually represent aspects of nature, and rituals and sacrifices aim to secure the weather needed for successful harvests. Monotheistic religions hold that God is a personal being and He directly intervenes in human history. God has ethical requirements about how His followers act, and will judge mankind accordingly. Thus Monotheistic religions tend to emphasize corporate and personal morality.

- Zoroastrianism

- Zoroastrianism was the religion of Persia (modern day Iran) before the coming of Islam. There is debate as to whether it is monotheistic or not. It teaches that the world is caught in a war between a good God and an evil God, but that the good God is destined to win. Our actions contribute to this cosmic struggle. Thus it is a belief system very much interested in ethics.

- The religion began with the prophet Zarathustra (Zoroaster in Greek) and teaches a final judgment, eternal life for the good, resurrection, and a place of eternal punishment for the evil. The commonalities with other monotheistic faiths is clear. There are only several thousand adherents to this religion today, mostly in Iran and India.

- Gradually, these nomadic people began to settle down, practice agriculture, and integrate with the indigenous people living in South Asia. Iron tools helped them produce large surpluses of agriculture. As they abandoned their nomadic lifestyles and became more urban, the sacrificial system outlined in the Vedas began to seem less relevant. Holy men who lived outside of towns and villages practiced aestheticism and drew followers, or disciples. These teachers were outside the official religious practices and focused more on philosophical issues, such as the meaning of life and what man's place in the universe is. The teachings of these holy men formed the basis of a body of teachings called the Upanishads and they mark the end of the Vedic period. The core of the Upanishads, the teachings about karma, atman, and reincarnation, would be integral to the formation of Hinduism in the classical age.

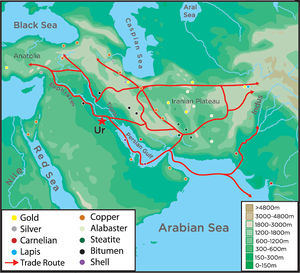

- F. Individual human beings have always traded things of value among themselves. As basic as this sounds, this is the beginning of economic exchanges. When urban societies developed these exchanges become more complex; laws were devised to regulate trade and often a class of people, called merchants, developed to preside over large economic exchanges. Initially, farmers and artisans would bring beads, textiles,agricultural produce and pots to the cities. As cities become aware of each other they traded among themselves, thus expanding buying and selling from local to regional levels. With the grown of civilizations in the valleys of major rivers, trade expanded to transregional (across regions) exchanges and included both land and maritime routes (see map on the left.) Some notable exchanges between early civilizations include the following.

- F. Individual human beings have always traded things of value among themselves. As basic as this sounds, this is the beginning of economic exchanges. When urban societies developed these exchanges become more complex; laws were devised to regulate trade and often a class of people, called merchants, developed to preside over large economic exchanges. Initially, farmers and artisans would bring beads, textiles,agricultural produce and pots to the cities. As cities become aware of each other they traded among themselves, thus expanding buying and selling from local to regional levels. With the grown of civilizations in the valleys of major rivers, trade expanded to transregional (across regions) exchanges and included both land and maritime routes (see map on the left.) Some notable exchanges between early civilizations include the following.

- Between Mesopotamia and the Indus Civilization Surpluses of agriculture in the southern area of Mesopotamia produced large populations and more complex social classes. Yet the region lacked metals necessary for more advanced tools and the new urban elites desired “prestige materials” to showcase their personal wealth and status. Contact with the Harappan society of the Indus River region met these needs. Merchants carried metals and semi-precious stones such as lapis lazuli from the Indus valley to eager markets in Mesopotamia. [2] When maritime routes emerged, bulk items like cotton textiles, grain and timber where traded. Mesopotamians traded terra-cotta pots, gemstones and pearls. Trade was facilitated by written contracts and enclaves of merchants which developed along the routes. Mesopotamian seals, used to sign negotiated trade agreements, have been found in the cites of the Indus valley.

An Akkadian seal drawn by artist Audrey McIntosh. It depicts water buffalo that were traded from the Indus to Mesopotamia.[1]

An Akkadian seal drawn by artist Audrey McIntosh. It depicts water buffalo that were traded from the Indus to Mesopotamia.[1]

- Between Mesopotamia and the Indus Civilization Surpluses of agriculture

- Between Egypt and Nubia The powerful Egyptian state along the Nile also engaged in trade. The monarchs of Egypt longed to control the region called Nubia to the south of them. At this time in history, Nubia was the only place in sub-Saharan Africa known to the outside world. Homer referred to it as the "remotest nation." The coveted trade items of sub-Saharan Africa, most notably ivory, gold and slaves, made their way north through the land of Nubia. Although they sought to exploit this trade corridor, the Egyptians despised Nubian people and culture and had no desire to occupy it.

- The trade between Egypt and Nubia brought many Egyptian cultural and political practices to the states of Nubia. Their political structure resembled that of the pharaohs; Nubians adopted hieroglyphs, the Egyptian system of writing; they built pyramids as burial tombs; and their god Amun was a direct borrowing from Egyptian religion. Thus trade became the vehicle of cultural and political interaction between urban societies.

- Between Egypt and Nubia The powerful Egyptian state along the Nile also engaged in trade. The monarchs of Egypt longed to control the region called Nubia to the south of them. At this time in history, Nubia was the only place in sub-Saharan Africa known to the outside world. Homer referred to it as the "remotest nation." The coveted trade items of sub-Saharan Africa, most notably ivory, gold and slaves, made their way north through the land of Nubia. Although they sought to exploit this trade corridor, the Egyptians despised Nubian people and culture and had no desire to occupy it.

- G. As these civilizations grew economically and demographically through trade, their societies became more stratified. The simple divisions of people into social classes became more complex. Patriarchal and hierarchical divisions, as we have seen, became reinforced through laws, religion, and custom.

- G. As these civilizations grew economically and demographically through trade, their societies became more stratified. The simple divisions of people into social classes became more complex. Patriarchal and hierarchical divisions, as we have seen, became reinforced through laws, religion, and custom.

- H. A significant development of civilizations during this period was literature. With the invention of systems of writing, stories that had been passed down orally could be written and shared more readily. Literature is not just about amusing stories. Widely held literary traditions reveal the unconscious assumptions people have about existence, morality, and the meaning of life. (Think of the Bible and Homer's writings.) Literature borrows its content from real life, gives form and interpretation to that content, then feeds those interpretations back into real life each time a story is read or told. It shapes the categories by which people organize the raw experiences of their lives and frames a society's concepts of heroism, ethics, and the human condition.

- H. A significant development of civilizations during this period was literature. With the invention of systems of writing, stories that had been passed down orally could be written and shared more readily. Literature is not just about amusing stories. Widely held literary traditions reveal the unconscious assumptions people have about existence, morality, and the meaning of life. (Think of the Bible and Homer's writings.) Literature borrows its content from real life, gives form and interpretation to that content, then feeds those interpretations back into real life each time a story is read or told. It shapes the categories by which people organize the raw experiences of their lives and frames a society's concepts of heroism, ethics, and the human condition.

- The earliest literary tradition we know of is the Epic of Gilgamesh. Originating from the Sumerians of Mesopotamia, it spread and was adapted to other nearby civilizations. The earliest complete extant version of this epic is the Babylonian version of the story. You can read the complete text HERE.

- The hero of the epic is Gilgamesh, who sets out to find the meaning of human life after his companion Enkidu dies, only to discover that eternal life is only for the gods. The mortality of mankind suggested in this story is in contrast to many other civilizations' belief in the afterlife during this same time. Some experts have suggested that this pessimistic cultural outlook might have been influenced by the harshness of Mesopotamian life, with its randomly flooding rivers, political disunity, and their lack of natural barriers to invaders. Nevertheless, the Epic of Gilgamesh reflects the culture of ancient Mesopotamians.

- The earliest literary tradition we know of is the Epic of Gilgamesh. Originating from the Sumerians of Mesopotamia, it spread and was adapted to other nearby civilizations. The earliest complete extant version of this epic is the Babylonian version of the story. You can read the complete text HERE.

- Another example of a literary tradition is the Rig Veda of the Ayrans in South Asia. The Rig Veda is the earliest of the collection of Vedas, or religious hymns, that characterize the Vedic Period in India's history. As we have seen above, the monotheism of the Hebrews tends to generate an exclusivist attitude in religious matters. On the contrary, one of the most salient lines in the Rig Veda is "Truth is one, but the wise speak of it in many different ways." Even in the earliest of the Vedas we see the beginning of an inclusivist religious culture that seeks to absorb other religious traditions in its search for the truth. This will later be a characteristic of Hindu culture.

References

- ↑ Civilizations in Contact http://www.cic.ames.cam.ac.uk/pages/mcintosh.html

- ↑ Civilizations in Contact http://www.cic.ames.cam.ac.uk/pages/mcintosh.html